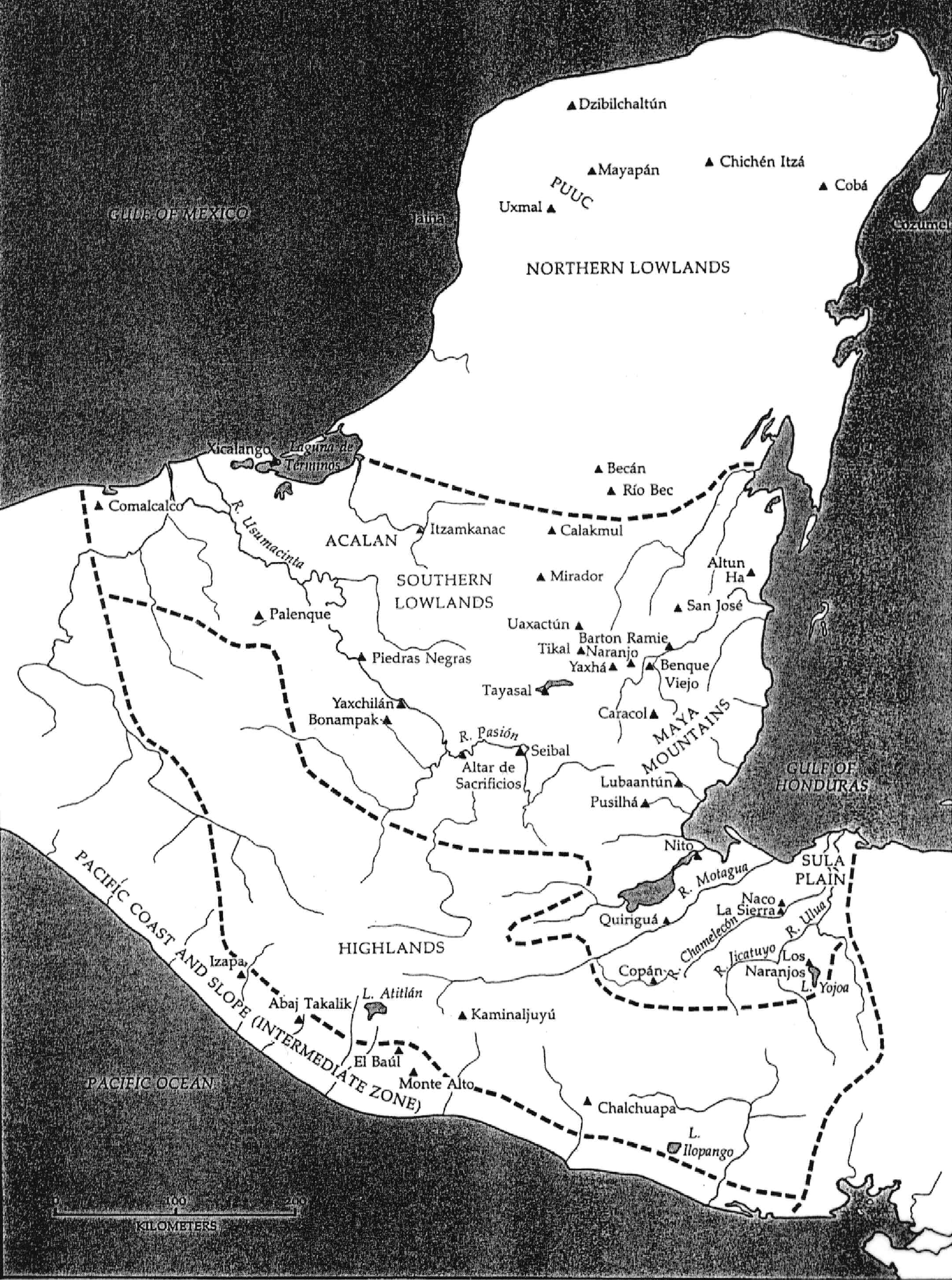

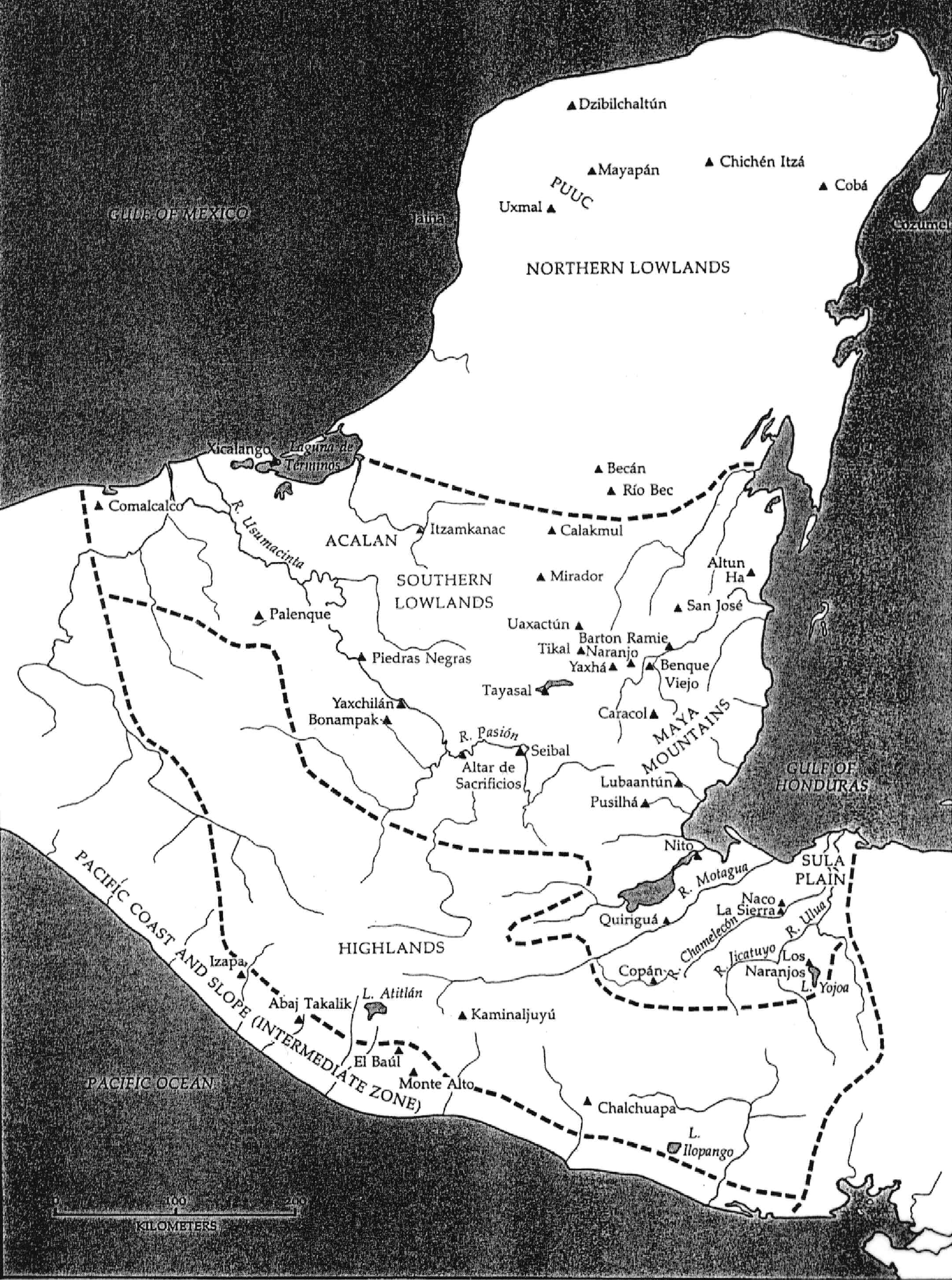

Map of the Maya area. After Henderson (1981:Map 3).

The time period most relevant to a study of the Maya codices is the Late Postclassic and subsequent conquest era (c. A.D. 1200-1540). By the beginning of the Late Postclassic period, Maya society had undergone significant changes resulting from the abandonment of Classic period centers in the Maya heartland (the Petén region of Guatemala) in the 9th century, followed by the collapse of cities in the northern area, including Chichén Itzá, between A.D. 900-1000. Large-scale architectural activity apparently ceased for more than a century, re-emerging with the construction of Mayapán and a series of centers along the Caribbean and southern Gulf coasts in the 12th century (see map below). Mayapán’s occupation has been dated from c. A.D. 1200 to 1441, but a series of smaller centers, including Tulum on the Caribbean coast and sites on the island of Cozumel, were still inhabited when the Spanish first encountered the Maya in the early 16th century.

Map of the Maya area. After Henderson (1981:Map 3).

Despite the superior weaponry of the Europeans, the Maya proved difficult for the Spanish to conquer. The conquest of the Yucatán peninsula spanned almost 20 years (from 1527 to 1546), and the Itzaj Maya capital of Ta Itzá (or Tayasal, as it was known to the Spanish) was not conquered until 1697. Subjugating the Maya of Tayasal was especially challenging for the Spanish armies because of their remote location on an island in Lake Petén Itzá in the heart of the Petén in present-day Guatemala.

We know from Spanish sources, principally Diego de Landa, the second Bishop of Yucatán, that codices were being written at the time of the conquest. Moreover, despite the efforts of Bishop Landa and the Inquisition to destroy all traces of idolatry (including hieroglyphic writing), codices were still secretly being used for several generations after the conquest.

The Spanish chroniclers provide several early descriptions of Maya books. The first appears to have been written by Peter Martyr in 1520 and concerns the Royal Fifth sent by Hernan Cortés to the Spanish king Charles V from Veracruz, Mexico. (Martyr was a historian based in Valladolid, Spain who was on the receiving end of shipments sent from the Americas.) On the basis of his description, Eric Thompson was of the opinion that Martyr “saw and described Maya books.” Michael Coe suggests that these were the same codices that Cortés collected on Cozumel in 1519, as reported in Martyr’s account.

Other first-hand descriptions of Maya codices from 16th and early 17th century Yucatán include those written by Landa as well as other Spanish chroniclers. Later accounts include those of Avendaño y Loyola. Writing at the end of the 17th century, he describes bark paper books containing native calendars and prophecies in terms suggesting that he saw them first-hand: “... I had already read about it in their old papers and had seen it in their anahtes which they use, which are books of the barks of trees, polished and covered with lime, in which by painted figures and characters, they have foretold their future events.”

Hieroglyphic manuscripts were not limited in their distribution to the northern lowlands during the Colonial period. Several, for example, were found at Tayasal following its defeat to the Spanish in 1697. Reports indicate that some of these were taken by Ursua, the captain of the Spanish forces, although their present whereabouts are unknown. Divinatory almanacs were still being used by the Quiché of highland Guatemala during this time period as well, as suggested by the writings of Francisco Ximénez, who described books with divinatory calendars “with signs corresponding to each day.” According to Dennis Tedlock, these books may have been similar to the Ajilab’al Q’ij (Count of Days), a Quiché manuscript dated to 1722 that contains alphabetic versions of 260-day almanacs like those found in the surviving Maya hieroglyphic codices.

Copyright (c) 2002-2018 by Gabrielle Vail, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Click here for information on how to cite to this website in a publication.