Information in the Maya codices is formatted in one of two ways—what epigraphers call tables and almanacs. The two may be distinguished in that tables contain dates in the Long Count calendar, whereas almanacs generally only record tzolk'in dates (see Glossary for a definition of terms). The Madrid Codex is composed entirely of almanacs, meaning that there are no Long Count dates in the manuscript that allow it to be placed in absolute time. This is in contrast to the Dresden Codex, which contains a series of tables referencing astronomical events such as eclipse cycles and the appearance and disappearance of Venus in the sky, as well as seasonal cycles (solstices and equinoxes). For an agriculturally-based society like the Maya, tracking seasonal events was extremely important.

Although Long Count dates are not found in the Madrid Codex, seasonal and astronomical references occur in a number of almanacs. These data can, according to a methodology developed by Victoria and Harvey Bricker, be used to date the almanacs containing these types of references in real or absolute time. Their model of how almanacs functioned differs significantly from the traditional interpretation of almanacs as instruments for divination and prophecy within the tzolk'in calendar that remain unanchored in real time. Another model, recently formulated by Gabrielle Vail, provides a further challenge to the traditional interpretation of the structure and function of codical almanacs.

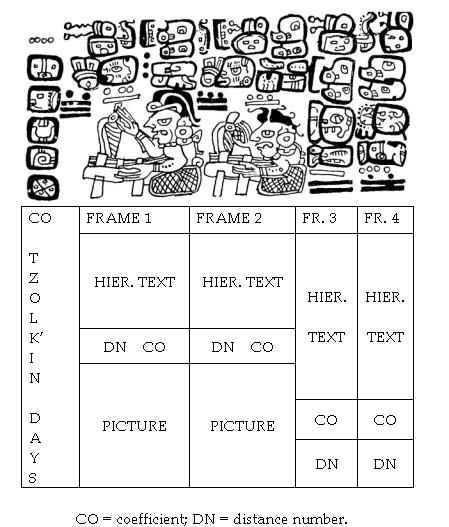

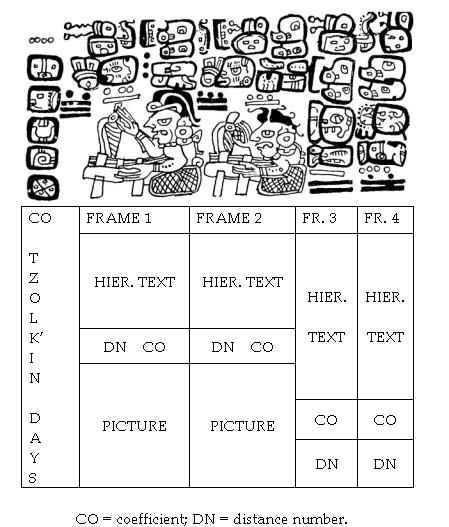

The majority of almanacs in the Maya codices have a similar format. They are divided into a series of frames, which generally include a hieroglyphic caption, bar-and-dot numbers, and a picture. The initial date of an almanac is determined by the column of day glyphs to the left of the frames. It includes a bar-and-dot coefficient which applies to each of the day glyphs in the column below it. Each of these dates represents the start of a new row of dates associated with the almanac.

Most almanacs have either four, five, or ten day glyphs in the introductory column. Because they are based on a 260-day period, the first type may be said to have a 4 x 65-day structure; the next to have a 5 x 52-day structure; and the last to have a 10 x 26-day structure. The first number refers to how many day glyphs are in the introductory column, and the second to the total reached by summing the black bar-and-dot numbers associated with each frame. The black numbers specify distance numbers or intervals, and the red numbers (represented by an outline in black and white drawings) are coefficients associated with day names.

The calendrical information contained in an almanac appears in a very abbreviated form. The only information given explicitly consists of the initial dates in each row (which appear in the tzolk'in column at the beginning of the almanac). Together with the distance numbers and coefficients, this information allows the reader to determine the complete calendrical structure of an almanac.

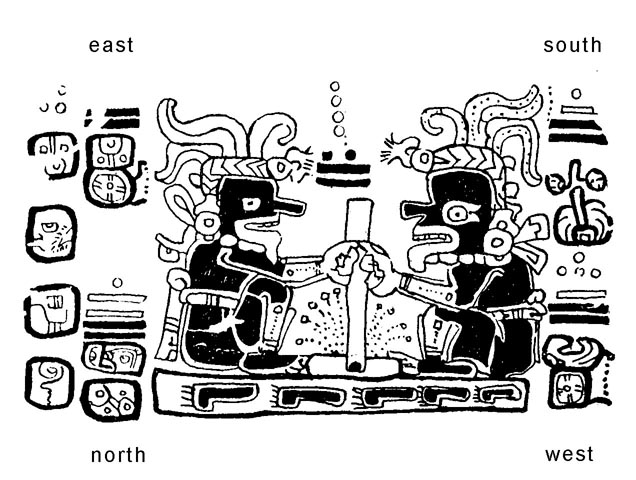

Almanac on Madrid 16a. After Anders (1967). Courtesy of the Museo de

América, Madrid.

The almanac on Madrid 16a illustrated above begins on the tzolk'in date 4 Ahaw (uppermost in the tzolk'in column), which is associated with the picture and text in the first frame. One then adds 15 days, as indicated by the first distance number (in black), to arrive at the date associated with the second frame (which consists of text without a picture). Adding 15 to 4 results in 19; because the days of the tzolk'in cannot be numbered above 13, this number (13) must be subtracted from 19 to arrive at the correct coefficient—6 (Men). The “6” is recorded in the almanac (following the black “15”), whereas the day glyph (Men) is calculated by counting forward 15 days from Ahaw. Ten days are then added to reach the date associated with the almanac’s third frame, 3 (Chikchan). Adding the next distance number, 11, brings one to the date associated with the almanac’s fourth frame, 1 (Kib’). This completes the first row of dates for the almanac. By adding the 16 indicated in the fourth frame (mistakenly drawn as an 11), one returns to the second day glyph in the initial tzolk'in column—4 Eb’. This date is associated with the almanac’s first frame, at the start of the second row. By continuing through all five rows of the almanac, a total of 260 days, or one tzolk'in cycle, is reached. Here is the complete structure:

| 4 + 15 | 6 + 10 | 3 + 11 | 1 + 16 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahaw | Men | Chikchan | Kib’ |

| Eb’ | Manik’ | Kab’an | Lamat |

| K’an | Kawak | Muluk | Ahaw |

| Kib’ | Chuwen | Imix | Eb’ |

| Lamat | Ak’b’al | B’en | K’an |

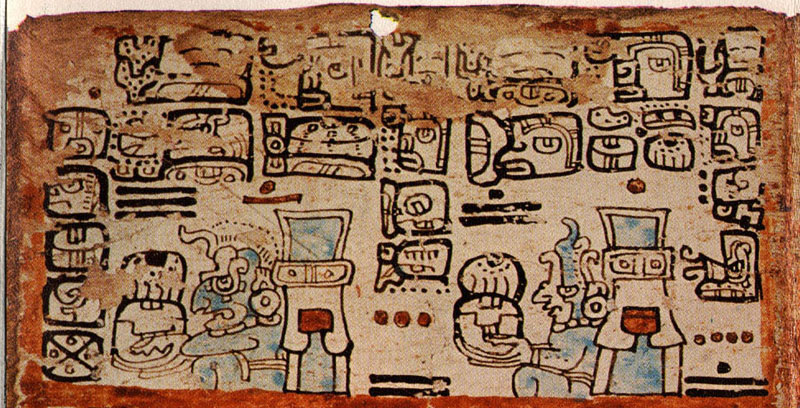

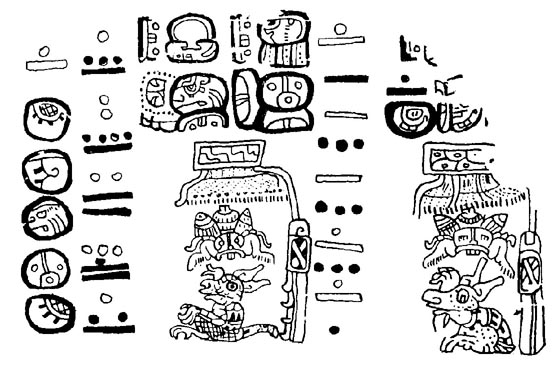

How did Maya daykeepers use almanacs such as this one? According to the traditional interpretation, each of an almanac’s frames is associated with a series of dates in the 260-day calendar that can be used for determining an appropriate day for the activity represented in that almanac. The almanac on Madrid 23c (see below), for example, includes three frames, two with pictures and one (frame 2) without. All three frames are associated with the activity of painting structures blue; this is performed by the creator Itzamna (frame 1); the death god Kimil (frame 2), and the rain deity Chaak (frame 3). According to the traditional model, 4 Ahaw, 4 Eb’, 4 K’an, 4 Kib’, and 4 Lamat are considered good days for this activity, since they are associated with the frame picturing Itzamna and the text caption “Itzamna, first [or honored] flower.” Twenty days later, however, the days 11 Ahaw, 11 Eb’, 11 K’an, 11 Kib’, and 11 Lamat corresponding with the second frame represent bad days for painting structures, since they are linked to a clause that names “the death god Kimil, the dead person.” The dates in the last frame are again considered propitious, as they concern the rain deity Chaak, who had extremely positive associations.

Almanac on Madrid 23c. After Anders (1967). Courtesy of the Museo de

América, Madrid.

| 4 + 20 | 11 + 17 | 2 + 15 |

|---|---|---|

| Ahaw | Ahaw | Kab’an |

| Eb’ | Eb’ | Muluk |

| K’an | K’an | Imix |

| Kib’ | Kib’ | B’en |

| Lamat | Lamat | Chikchan |

An alternate way of interpreting almanacs such as this one that include a series of frames with repetitive iconography (i.e., in which the activity remains the same but the deity changes) is proposed by Vail. She points out that the traditional model fails to take into account the fact that the use of blue paint to consecrate a house or structure has specific ritual correlates described in Bishop Landa’s account Relación de las cosas de Yucatan (written in the 1560s). A careful reading of Landa’s text suggests that blue paint was associated with ceremonies celebrated in conjunction with the 365-day haab', rather than with the tzolk'in calendar. This suggests to Vail that this almanac, as well as a number of other 5 x 52-day almanacs with similar iconography in each frame, refers to the repetition of haab' rituals over the course of a 52-year Calendar Round cycle. Codical almanacs such as those illustrated above, therefore, allowed Maya priests or daykeepers to schedule the same haab' ritual for a series of years over the course of a 52-year period. For more information about how this was accomplished, Vail (2002, 2004) offers a detailed discussion.

Support for Vail’s model is provided by references to haab' dates that occur in several almanacs in the Madrid Codex. These dates not only provide empirical evidence of the utility of this proposal, but they also suggest the importance that Maya scribes attached to anchoring at least certain events to cycles of time beyond the 260-day tzolk'in. In a recent publication, Vail and Victoria Bricker discuss other haab' dates that have been identified in several Madrid almanacs, including Madrid 34-37 and Madrid 65-73b.

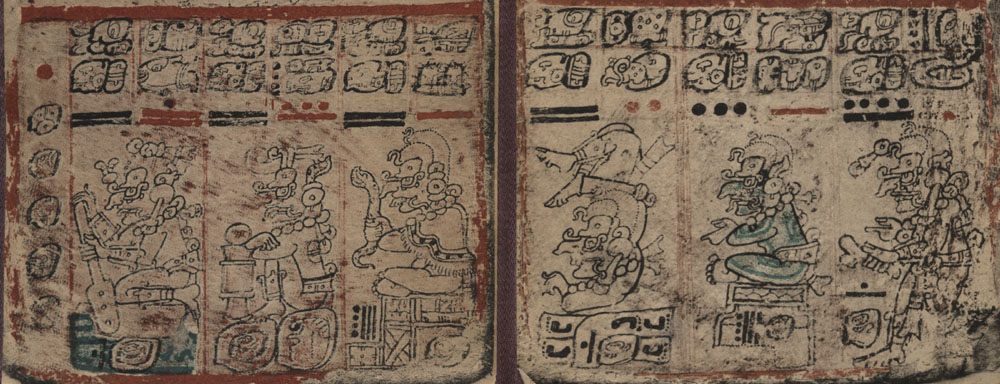

Following Vail’s model, almanacs in the Maya codices may be grouped into two sets—those that picture the repetition of the same activity from frame to frame, which may be interpreted as Calendar Round (52-year) instruments, and those that show a sequence or progression of activities that seem to occur within the time frame of a single or double tzolk'in (260-day) cycle. The almanac on Dresden 40c-41c, for example, pictures Chaak in various locations, as specified in the glyphic text. These include the water (frame 1), a maize field (frame 2), the sky (frame 3), etc. Note that each of these pictures is separated from the one that follows by an interval of ten days (represented by the black bar-and-dot numbers in the illustration below).

Almanac on Dresden 40c-41c. After Förstemann

(1880).

Not all almanacs in the Maya codices are formatted in terms of an initial column of tzolk'in dates followed by discrete frames associated with a single distance number and coefficient. Three other structural types occur fairly commonly in the Madrid Codex—circular, crossover, and in extenso almanacs. Circular almanacs generally include a central picture with a series of distance numbers and coefficients placed around the image. In the example illustrated here, what would be presented as five separate frames in a more standard almanac format are reduced to one picture and four abbreviated hieroglyphic captions referring to the world directions.

Circular almanac on Madrid 51a. Drawing after Villacorta C. and Villacorta (1976:326).

Crossover almanacs resemble the more standard almanac format, except that each of the two frames is associated with a series of distance numbers and coefficients. These are read back and forth, generally beginning in the upper left (i.e., from frame 1, to frame 2, back to frame 1, etc.). Crossover almanacs are less common than circular almanacs in the Madrid Codex. Both types occur only very rarely in the other Maya codices, although they are also found in the central Mexican codices of the Borgia group.

Crossover almanac on Madrid 103a. Drawing after Villacorta

C. and Villacorta (1976:430).

In extenso almanacs have only recently been recognized as a significant structural type within the Madrid Codex. The Latin phrase in extenso refers to almanacs that explicitly depict all 260 days of the ritual calendar rather than highlighting only certain ones. In 1961, Anton Nowotny coined the term in extenso to describe a subset of such almanacs in the central Mexican Borgia group codices. As Nowotny defined them, Mexican almanacs recording 260 days occur in both a rectangular and tabular format. The in extenso type refers to almanacs that have a rectangular layout of five rows of 52 day signs (5 x 52 days = 260 days). Bryan Just discusses examples of similar almanacs in the Madrid Codex, found on pages 12b-18b, 65-73b, 75-76, and 77-78. They display a variety of formats. The first, on Madrid 12b-18b, can be compared to the almanac found on pages 1-8 of the Borgia Codex, whereas Madrid 75-76 has long been recognized as cognate with the almanac on page 1 of the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer from the Borgia group. Structural and calendrical correspondences among the Maya and central Mexican codices raise a number of interesting questions about scribal interaction across cultural boundaries during the Late Postclassic period in Mesoamerica.

Copyright (c) 2002-2018 by Gabrielle Vail, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Click here for information on how to cite to this website in a publication.